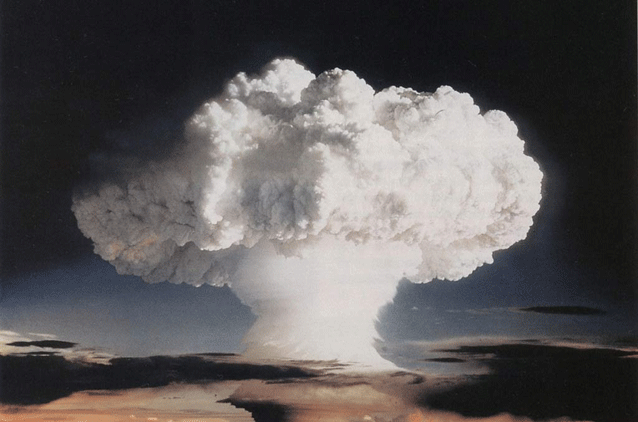

An atmospheric nuclear test conducted by the United States at Enewetak Atoll, Marshall Islands, on 1 November 1952. Credit: US Government

By Thalif Deen

UNITED NATIONS, Dec 7 2017 (IPS) – The Pacific islands have long remained victims of nuclear crimes – but the perpetrators, three of the world’s major powers with permanent seats in the UN Security Council, never paid for their deadly sins.

The testing grounds in the Pacific, included the Marshall Islands (Bikini and Enewetak), and also Johnston Atoll and Christmas Islands in Kiribati.

The so-called “Pacific Proving Grounds”, which included the Marshall Islands and a few others on the Pacific Ocean, was the site of US nuclear testing between 1946 and 1962.

France tested its weapons on Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls in French Polynesia, with French naval vessels clashing with Greenpeace anti-nuclear campaigners.

The United Kingdom, along with the US, conducted several nuclear tests in and around Kiribati in the late 1950s. But the islanders were not evacuated exposing them to radiation from the blasts.

All of these tests, which left behind environmental hazards and radioactive waste, came to an inglorious end – or so it seems. But the nuclear nightmares over the Pacific continue to linger on.

According to the London Guardian, the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal awarded more than $2.0 billion in personal injury and land damage claims arising from the nuclear tests, but stopped paying after a compensation fund was exhausted.

After 67 tests, US nuclear experiments in the Marshall Islands ended in 1958. But in a 2012 report, UN Special Rapporteur Calin Georgescu, said “near-irreversible environmental contamination” had led to the loss of livelihoods and many people continued to experience “indefinite displacement”.

And a projected sea-level rise, triggered by climate change, is threatening to unearth the radioactive waste and spill it into the high seas.

According to two researchers, Barbara Rose Johnston and Brooke Takala Abraham, U.S. medical scientists traveled to the Marshall Islands, for nearly four decades, in order to document degenerating health and conduct related experiments, “all without informed consent.”

All told, 1,156 men, women, and children were enrolled in studies exploring the acute and late effects of radiation.

Among the findings of this research: radiation exposure generated changes in red blood cell production and subsequent anemia; metabolic and related disorders; musculoskeletal degeneration; cataracts; cancers and leukemia; and significant impact on fertility as evidenced by miscarriages, congenital defects, and infertility.

“Their experiences also demonstrate how chronic and acute radiogenic exposure compromises immunity, creating population-wide vulnerability to infectious and non-communicable disease”, Johnston and Abraham wrote.

Bob Rigg, a former senior editor with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons and ex-chair of the New Zealand National Consultative Committee on Disarmament, told IPS: “It is impossible to make sweeping generalisations about the entire Pacific region, which is both vast and diverse”.

But US attention, he pointed out, was focused in particular on Micronesia, which includes most of the islands bitterly fought over in the latter years of World War II.

“The US wields disproportionate influence over this sub-region, where most of its 1,054 nuclear tests were conducted,” he added.

The US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, said Rigg, can be defined as the first example of US nuclear testing, given that a principal motive for both attacks was to facilitate large-scale research into the effects of nuclear weapons on living human beings, a subject which was a closed book even to the world’s leading nuclear scientists at the time.

As soon as the war ended, he said, “the US hastened to establish political control over a number of strategically important islands forming an “island chain” in the Pacific – a chain of US military and political influence cementing US control of major trade routes, while also enables it to contain the growing power and influence of Communist China.”

Ironically enough, the US island chain has something in common with China’s South China Sea outposts which today draw the ire of the US, he added.

Robert Alvarez, an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington D.C. and an Adjunct Professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced Strategic International Studies, told IPS that three major international conferences—in Oslo, Mexico City, and Vienna— focused on the humanitarian effects of nuclear weapons, and on establishing a new international legal instrument that would outlaw nuclear weapons.

The humanitarian initiative and the Marshall Islands lawsuits—including one in US federal courts and the other with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague — received a chilly, some might say hostile reception from the nuclear weapons states, for an understandable reason, he pointed out.

The nuclear weapons countries are engaged in costly modernization efforts that all but guarantee the continued existence of nuclear weapons for decades, and perhaps beyond. The Marshalls lawsuits and the humanitarian initiative both seek to make the nuclear states seriously negotiate toward nuclear disarmament, he noted.

In an article in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists back in May 2015, Alvarez said the damage did not end with nuclear testing.

In the 1960s, islands of the Enewetak Atoll were stripped of topsoil and used for explosive crater experiments, to see how US missile silos would hold up to enemy missiles.

And in October 1968, the US Navy conducted a biological warfare experiment in which Staphylococcal enterotoxin B, a virulent bacterium, was released over the Enewetak Atoll from fighter aircraft.

“The pathogen proved to be harmful to experimental animals over a 1,500 square mile area. Since the late 1950s, the Kwajalein Atoll and lagoon have served as an anti-ballistic missile launch site for testing against possible missile attacks,” he noted.

Nearly every US intercontinental ballistic missile was test fired at Kwajalein. Now home to the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site, the $4 billion US Air Force complex on Kwajalein is considered a key strategic asset for anti-ballistic missile testing, military space projects, and intelligence gathering, wrote Alvarez, who was also a Senior Professional Staff member for the U.S. Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, where he conducted an investigation into the conduct of the U.S. nuclear weapons program in the Marshall Islands.

Rigg told IPS Truman had no qualms about bombing Japan and seizing control of several Micronesian Islands where America’s many subsequent nuclear tests could be conducted. Indigenous populations were frequently marginalised, displaced, and impoverished.

Traditional ways of living, cultivating food and eating were frequently replaced within one generation with a barbarised version of US consumer culture. The key operational assumption was that Pacific Islanders represented an inferior culture which, in the patronising words of one US scientist, at least had more in common with civilised westerners than laboratory mice, he said.

“Like the Japanese, Pacific Islanders were viewed through the prism of mainstream US racism. The example of Rongelap Island, which was seriously affected by fallout from the huge Castle Bravo test, is perhaps most instructive.”

When the islanders repeatedly lobbied for permission to return to their home, said Rigg, the US Atomic Energy Commission declared it safe for re-habitation, with US scientists privately noting that “the habitation of these people on the island will afford most valuable ecological radiation data on human beings.”

As a major environmental polluter, he argued, the US contributes to global warming which disproportionately affects many small Pacific Island states whose highest point is in some cases just a couple of metres above sea level.

“Such islands are also acutely vulnerable to the climate change-induced violent storms which increasingly inflict massive destruction on both vegetation and homes. As many of these islands are desperately poor there is all too often no money to rebuild infrastructure and homes, with more than 95% of damaged buildings being uninsured.”

Trump’s America First policy has already produced a 30% cut in State Department funding which will dramatically curtail expenditure on Pacific islands which are not part of the militarised US island chain. Australia abjectly proclaims that it is “joined at the hip” with the US, slavishly following in the wake of Uncle Sam in all things, Rigg said.

“Fortunately, there is one small ray of hope: New Zealand has just elected a new Labour Government which is signalling its willingness to adopt innovative approaches to political problem-solving, including in the region.”

The new Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, he pointed out, has already signalled her government’s willingness to view Pacific Islanders fleeing their submerged islands as refugees. At present Australia’s immigration policies exclude such “environmental refugees.”

This New Zealand initiative could eventually necessitate the re-negotiation of the UN Convention on Refugees, to accommodate a new category of environmental refugees, he added.

In the words of a recent report to a congressional committee, even before the election of Trump, the US had pursued a “policy of benign neglect towards the South Pacific nations.

“Too often have we relied on Australia and New Zealand to determine what US policy should be in the region.” If this was true before Trump, it will be doubly true now.”

Possibly with at least some support from New Zealand, Pacific Island states will have to continue to seek political support from outside their region, as recently, when Fiji and Germany jointly hosted the November meeting of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP23) in Bonn.

The elevation of Fiji to this prominent role reveals that, in the complete absence of support from both Trump’s US and Malcolm Turnbull’s Australia, there is a heartening emerging international awareness of the extent to which the very existence of some Pacific Island states is already under threat from climate change, he noted.

“But words must be backed up by large quantities of hard cash, without which some small Pacific Island states will undoubtedly go under.”

This article is part of a series about the activists and communities of the Pacific who are responding to the effects of climate change. Leaders from climate and social justice movements from around the world are currently meeting in Suva, Fiji, through 8 December for International Civil Society Week.

The writer can be contacted at thalifdeen@aol.com

© Inter Press News Service. Reprinted with Permission. Original post here.